In Grosse Fatigue (2013), Camille Henrot (b. 1978) attempts to not only understand the chaos of history, but also to visualize this disarray. Created as part of her residency at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, the video depicts various archival activities at the Smithsonian along with active browser search windows as an unidentified narrator rhythmically stitches together origin myths from disparate geographic locations and cultural traditions. Henrot follows anthropologists, conservators, and office workers as they reveal the organizational structure of the institution, with its drawers of taxidermy animal specimens, computer archives, and office corridors. These mundane physical and architectural frameworks—constructed to contain an incomprehensible body of knowledge—are ultimately only able to describe isolated areas of human experience and achievement.

Grosse Fatigue attests to our unending attempts to conceptualize the universe with the constantly expanding cosmos of the digital realm. As the narrator’s voice spirals into an ecstatic flow of eschatological outbursts, browser windows overlap with countless image searches, Wikipedia pages, and open art catalogues. Henrot’s faceless protagonist guides us through the museum without a terminal goal, browsing with the same freedom, if not the same aimlessness, as time spent online. However, Grosse Fatigue evades hopelessness in the face of the weight of human knowledge, whether in the museum or in more virtual archives. Highlighting the limitations of various disciplines, meta-narratives, and creation myths, Henrot also demonstrates the ways in which we necessarily navigate, appropriate, and amalgamate these systems in order to understand our world.

Grosse Fatigue, 2013

Single-channel video, sound, color; 13 min

Courtesy the artist, Silex Films, and kamel mennour, Paris

Ed Atkins (b. 1982) creates video installations that consider the relationship between body and screen, contemplating the ways in which our immersion in a landscape of increasingly sophisticated digital imagery has altered the meaning of materiality. In his videos and writings, which are often presented together in his installations, Atkins constructs a theory of HD technology and its implications for the nature and definition of matter, pointing to what he describes as the “deathliness” of the HD image in spite of its capacity to seamlessly reproduce the living world.

Happy Birthday!! (2014) takes as its point of departure a drawing by the artist, writer, and philosopher Pierre Klossowski that depicts an ambiguous scene of a man hovering over a sickbed and cradling the head of its occupant in a manner that seems at once tender and menacing. The video is presented entirely in ghostly grayscale and features the central figure of a man whose body repeatedly disintegrates or dematerializes. Along-side a soundtrack of Elvis Presley’s “You Were Always on My Mind,” a melancholy ballad of love lost, the figure speaks in fragmentary numerical phrases and references to temporal positioning, alluding perhaps to a meditation on memory and loss. In the narration of the video, Atkins constructs an elusive dialogue about the shifting context of numbers as both abstract, universal representations and “the most exquisite, personal metaphors” that represent birthdays, death dates, anniversaries, and bank accounts. Pointing to the multiple meanings of the word “digit”—both a number and a bodily appendage—the text draws together the CGI body, encoded in binary, and the human hand.

Happy Birthday!!, 2014

HD video, 5.1 sound; 6:32 min

Courtesy the artist and Cabinet Gallery, London

Pipilotti Rist’s (b. 1962) mesmerizing works envelop viewers in vibrantly colored kaleidoscopic projections that fuse the natural world with the technological sublime. Referring to her art as a “glorification of the wonder of evolution,” Rist maintains a deep sense of curiosity that pervades her explorations of physical and psychological experiences. Her works bring viewers into unexpected encounters with the textures and forms of the living universe.

4th Floor to Mildness (2016), shot largely underwater, is projected onto two screens hanging from the ceiling. The installation also comprises several beds scattered throughout the space, offering viewers an opportunity to immerse themselves in the work while lying alongside one another. In 2005, Rist created a digital fresco titled Homo Sapiens Sapiens to fill the entire ceiling of an eighteenth-century church in Venice, Italy. 4th Floor to Mildness similarly merges spirituality and enchantment, and includes images of floating bodies that update the iconography of Baroque ceiling frescoes.

Like many of Rist’s works, 4th Floor to Mildness juxtaposes domestic and public space, interior and exterior, to explore both the social and meditative aspects of image consumption: the installation combines the collective viewing typical of the cinema with the isolating use of computer screens and tablets. As Rist observes, “Today, with computers, TVs, and mobile phones, everything is flat and put behind glass—our feelings, histories, longings. We’re all separated from each other, for the human being that we are in contact with is always behind glass...But with art, we can jump out of our loneliness.”

4th Floor to Mildness, 2016

Video and sound installation 8:11 min / 8:11 min / 7:03 min / 6:19 min

Music and text by Soap&Skin/Anja Plaschg, courtesy Flora Musikverlag and [PIAS]Recordings

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Luhring Augustine, New York

Cheng Ran (b. 1981) has been producing film and video works that draw widely from Western and Chinese literature, poetry, cinema, and visual culture, fabricating new narratives that combine myths and historical events. Cheng’s earliest works, shot entirely in the confines of his apartment, attempted to make the ordinary aspects of his immediate environment into compelling subject matter for his films. Inspired by filmmakers such as Werner Herzog, Jim Jarmusch, and Béla Tarr, Cheng’s subsquent films and videos often registered his curiosity as he observed the overlooked and incongruous aspects of everyday life and chronicled his interactions with remote and historic sites.

Cheng’s multi-channel video series, Diary of a Madman (2016), borrows its title from what is widely considered China’s first modern short story, written by Lu Xun in 1918. Just as Lu Xun’s story comprises first-person narratives of a character at the margins of society who gradually succumbs to madness, Cheng’s videos take the form of diaristic vignettes that reveal a larger assessment of a foreign place through the eyes of an outsider. As a first-time visitor to the United States, Cheng approached New York with an awareness of iconic and cinematic images of the city, and a desire to find and capture what is typically excluded from such views. The videos include imagery from his early morning explorations of New York City streets, a trip to the Staten Island Bay, and a visit to an abandoned psychiatric hospital on Long Island, all of which expose his sense of estrangement amid these encounters with uncelebrated and obscure facets of the city.

Diary of a Madman, 2016

4:25 / 4:30 / 5:37 / 5:34 / 5:54 / 3:50 min HD Sound Video, Stereo Sound, Colour

All works courtesy the artist, K11 Art Foundation, and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing and Lucerne

In his absorbing short films, Kahlil Joseph (b. 1981) conjures the lush and impressionistic quality of dreams with particular reverence for quotidian moments and intimate scenes. Fly Paper (2017) is a film that departs from Joseph’s admiration of the work of Roy DeCarava (1919–2009), a photographer and artist known for his images of celebrated jazz musicians and everyday life in Harlem. Joseph’s film also touches on themes of filiation, influence, and legacy, marking a personal reckoning that intuitively calls upon his connections to the city through his family—and in particular, his late father, whom he cared for in Harlem at the end of his life. Fly Paper’s dynamic yet contemplative mood also builds on Joseph’s sense that layers of lived experience—and stories—are sedimented in the places that have played host to the aspirations and daily lives of countless individuals.

Harlem’s renown as the epicenter of black culture in the US is at the heart of Fly Paper, which builds on an interplay of artistic forms as much as it engages Joseph’s relationship to the accomplished black community who call New York home. Through various references to literature and narration, Fly Paper also probes the ways in which the literary imagination parallels that of film and how the ordinary act of storytelling shapes larger histories and enduring myths. Fly Paper moves beyond the visible by expanding Joseph’s practice into sound, unfolding a complex acoustic environment throughout which sonic textures and original compositions resonate. As a rich and polyphonic portrait of black art and culture in New York City, Fly Paper invites a meditation on the slippery nature of memory, reverie, and the photographic image.

Fly Paper, 2017

HD video installation, sound; 23:17 min

Courtesy the artist

Klara Lidén (b. 1979) combines both constructive and destructive strategies in her sculptures and videos that transform preconceptions about architectural and public space. Her works often act as subversive incursions that challenge the relationship between individuals and the spaces that contain them; in them the artist appears as a recluse seeking thrills in an urban, seemingly post-apocalyptic environment while exposing the materials and political realities of the world around us.

In Der Mythos des Fortschritts (Moonwalk) [The Myth of Progress (Moonwalk)] (2008), Lidén incorporates an iconic dance to frame her peregrinations around New York. As artist, performer, and amateur-dancer, she moonwalks throughout the streets and highways of Manhattan by night. This somnambulistic glide, accompanied by a repetitive and eerie song by the Swedish band, Tvillingarna, is an awkward imitation of the “cool” dance form popularized by the international pop star Michael Jackson in the late 1980s—with whom Lidén shares a tendency toward androgyny and unabashed exhibitionism. The steady tempo of the artist’s pace and the granular lo-fi quality of the film at night accentuate the dreamlike quality of the work and mirror the emptiness of her nocturnal surroundings. The short video repeats itself on an endless loop, enforcing the isolation of the artist who interacts solely with the city streets that guide her. Lidén’s unclenching and restricted movement in facing back-ward while dancing forward, embodies what the artist describes in her work as an “unbuilding, recycling, or improvising new uses for what’s already been set up.”

Der Mythos des Fortschritts (Moonwalk) [The Myth of Progress (Moonwalk)], 2008

Digital video, sound, color; 3:30 min

Courtesy the artist; Galerie Neu, Berlin; and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

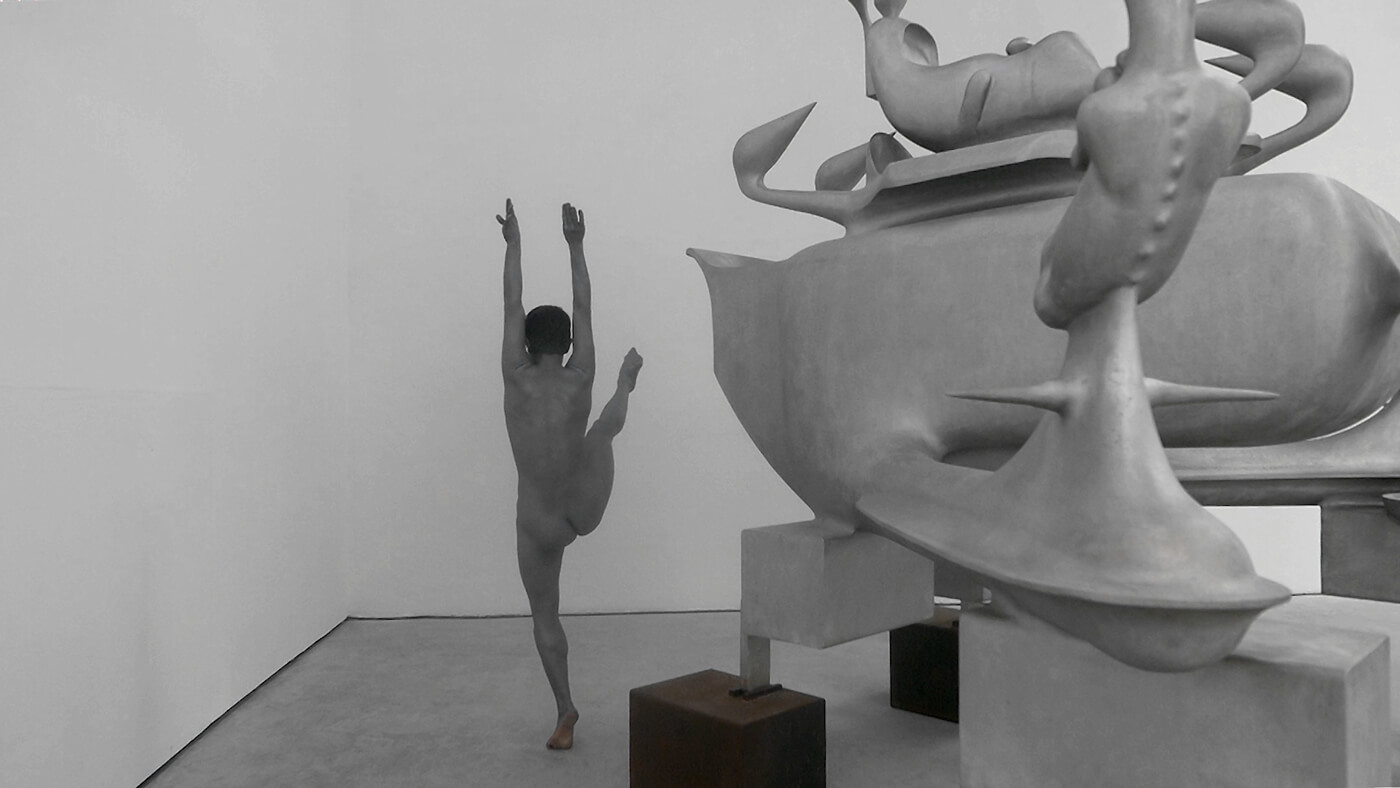

Lili Reynaud-Dewar (b. 1975) creates environments and situations in which she uses her own body, as well as those of others, to examine the vulnerability and empowerment associated with acts of exposing oneself to the world. Through a range of mediums such as performance, video, installation, sound, and literature, her works consider the fluid border between public and private space, and challenge established conventions relating to the body, sexuality, and power relations, especially as circumscribed by institutional space.

Over the course of a year, Reynaud-Dewar filmed herself dancing in theaters and various spaces across the United States and Europe where she was invited to exhibit, amassing a collection of videos titled TEETH, GUMS, MACHINE, FUTURE, SOCIETY (2016–17), which highlight a small part of the body: the teeth. In TEETH, GUMS, MACHINE, FUTURE, SOCIETY (One Body, Two Souls) (2017), one entry from the larger project, the artist calculatingly moves throughout an exhibition of the work of Austrian sculptor Bruno Gironcoli, taking her work’s subtitle directly from the title of Gironcoli’s show at CLEARING gallery in Brussels. The soft materiality of her own body, camouflaged in silver makeup, is set against the large metallic masses of Gironcoli’s sculptures. In this investigation, Reynaud-Dewar specifically focuses on the grill, a type of metal jewelry, mainly worn by rappers to bedazzle and protect their teeth. The artist envisions a futuristic transformation of her body, creating a situation in which the metal has invaded the surrounding space, moving beyond the constraints of the grill and Gironcoli’s sculptures.

TEETH, GUMS, MACHINE, FUTURE, SOCIETY (One Body, Two Souls), 2017

HD video, color; 4:34 min

Courtesy the artist and CLEARING, New York/Brussels

Wong Ping’s (b. 1984) animations are characterized by their riotously colorful and sardonically comical style. In his bizarre shorts, the artist combines personal biography, current events, and pure fantasy to reveal the absurdities he perceives lurking beneath the surface of his native Hong Kong, a city undergoing rapid political and cultural transformations. Wong’s phantasmagoric video diaries confront prevailing power structures, the effects of media saturation, and variant forms of physical and psychological domination.

Jungle of Desire (2015) was created in direct response to the pro-democracy street occupations and student protests during the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong in 2014, which exposed episodes of severe police brutality. The video’s protagonist, a penniless and impotent animator, concocts a twisted revenge fantasy on his sex-worker wife’s newest customer, a corrupt police officer who refuses to pay for her services. Intrigued by a local news report of a murdered woman in similar circumstances who had been supporting an extended family with “at-home” sex work, Wong constructed a narrative that drew upon this story and his own accounts of witnessing the police crack down on political protestors. Jungle of Desire’s bleak and scandalous pretext is offset by the animation’s lighthearted tone and intentionally puerile content and laced with a peculiar masochism that alludes to repressive cultural, moral, and ethical norms, as well as the autocratic strictures of daily life in Hong Kong.

Jungle of Desire, 2015

Single-channel video animation, sound, color; 6:50 min

Courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery

Oliver Laric (b. 1981) explores the circulation, repetition, and transposition of images throughout history, using the revolution in image production and dissemination brought about by the internet as a means to consider themes of authenticity, originality, and authorship. Linking the classical past to the digital present, he emphasizes the centrality of the creative reuse of images to art and culture since the very beginnings of civilization, proposing a new image economy that privileges the collectively authored remix over the auratic original.

Laric’s practice revolves around his concept of “versions,” an iterative approach to art- making that collapses the distinction between an original and its copy. Laric produced Untitled (2014–15) by collecting and re-drawing dozens of clips from animated films, including those featuring characters in the process of physical transformation, changing into new forms or disguising their appearances for the purposes of protection or survival. Setting these clips against a white background, he constructs a seamless process of constant adaptation and evolution, as each figure fluidly morphs into the next.

Untitled, 2014–15

4K video, sound, color; 5:55 min

Courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin

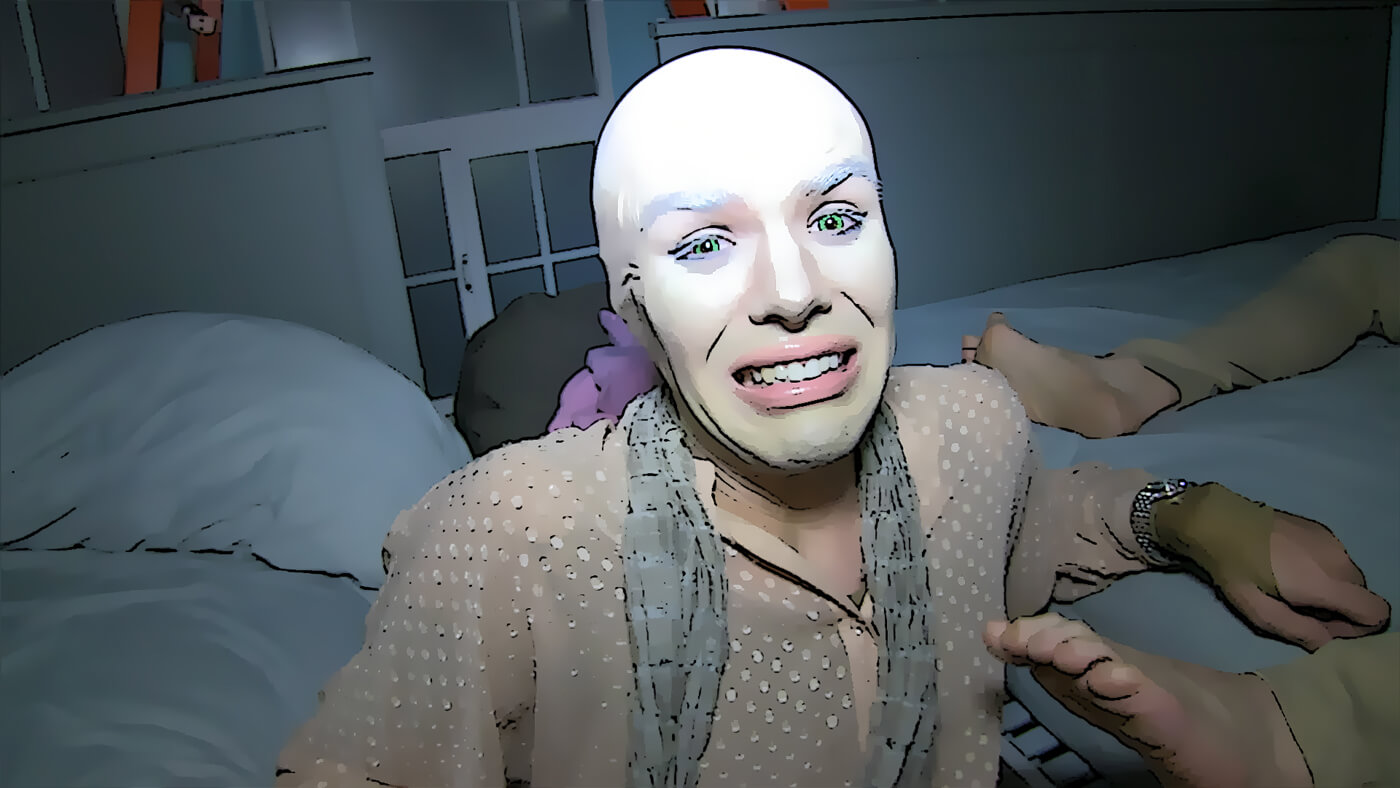

Wu Tsang’s (b. 1982) videos, installations, and performances explore how community and sociality shape subjectivity. Her feature-length experimental documentary Wildness (2012) depicts the Silver Platter, a historic bar for queer and trans Latinx people in Los Angeles that became host to a weekly party for a younger generation of queer artists of color. Tsang’s work often hinges on close collaborations. Girl Talk (2015), for instance, which was exhibited in the 2017 New Museum exhibition “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon,” features poet and theorist Fred Moten bedecked in a flowing caftan and crystalline crown, dancing in a backyard to a rendition of Betty Carter’s “Girl Talk” by musician Josiah Wise (serpentwithfeet). The brief slow-motion video posits identity as fluid and unfixed, tracing the contours of an intimate relational space shaped by blackness, transness, and queerness.

The Looks, also from 2015, is a sci-fi short–cum–performance document that opens with views of a futuristic cityscape—eerily glowing in unnatural shades of red, orange, and yellow-green—and a robotic voice intoning “It’s a beautiful day in the city of Tyrone.” Tsang’s frequent collaborator, boychild, plays Blis, a pop star overseen by the Looks, which Tsang has described as “digital avatars that control humans through a panoptical social media platform” (known as PRSM). Surveillance-style shots of Blis in bed contrast with footage of her coated in glitter, singing and dancing on stage for the official PRSM Channel and before a rapt audience—until a glitch gives way to a moment of rave-like euphoria. With The Looks, Tsang calls into question the liberatory potential often ascribed to technology and conjures a future marked by both dystopian social control and pockets of ecstatic freedom.

The Looks, 2015

Two-channel HD video, sound, color; 10 min

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi

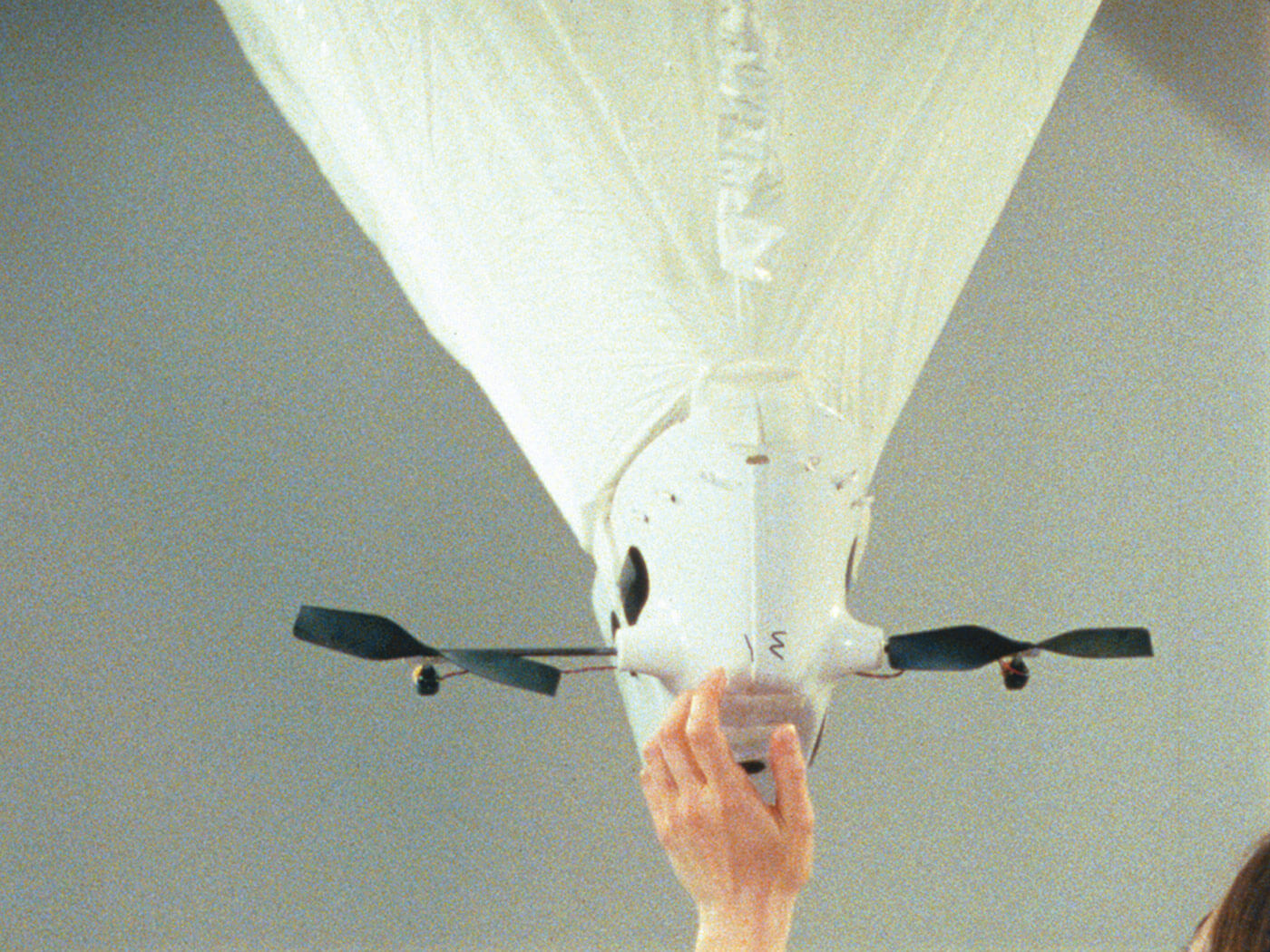

Daria Martin’s (b. 1973) films draw from sources such as early twentieth-century art, fashion, and dance to explore relationships between artistic mediums, between subject and object, and between the personal and the public. She sees in film an “invitation to travel through time and space within an imagined world,” often deploying older mediums, such as 16mm film projections, to consider contemporary concerns. Her short film Soft Materials (2004), for instance, was filmed in the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at the University of Zurich, and features robots—known as Eyebot, A-Mouse, and Dumbo—whose visible infrastructure and repeated movements recall Bauhaus constructions and performances.

Soft Materials is a study in textures, bodies, and objects. A solemn, pulsing soundtrack accompanies footage of metal gears grinding and wires moving back and forth—and nude humans watching this machinery in rapt concentration. A woman carefully picks up a small device and brings it to her face; its thin wires caress her cheek in an intimate meeting of human and technology. A man interacts with a robotic hand, its metal fingers curling around his bicep or sensually grasping at his lips. The film zooms in and out, from extreme detail—notches on the sides of gears, the pores on the woman’s face—to wider shots of human-machine interaction, raising questions of scale and the possibility of desire between robots and fleshly people, or what the title cheekily refers to as “soft materials.” While the film looks back to artists’ fascination with automation in early modernism, its focus on the subjecthood of objects and vice-versa resonates with more recent theoretical inquiries into how people and technologies interact.

Soft Materials, 2004

16mm film, sound, color; 10:30 min

Courtesy the artist and Maureen Paley, London

Cally Spooner’s (b. 1983) DRAG DRAG SOLO (2016) was produced on the last day of her New Museum show “On False Tears and Outsourcing.” Composed of site-specific architectural interventions that amplified certain qualities in the exhibition space by using a fifty-seven foot wall of acoustic panels, fluorescent daylight bulbs, and live radio, the exhibition was activated by seven dancers who, throughout museum opening hours, carried out a conflicted choreography.

Trained by rugby players and a movie director, and following the logic of a “stand-up scrum”—a daily meeting often used in collaborative work practices such as software development or advertisement—the dancers acquired techniques in attack, defense, and seduction found in contact sports and on-screen romance films. Responding to the New Museum Lobby Gallery’s glass wall and its condition of high visibility, the exhibition considered the characteristics of corporate and museum architectures alike.

For the video DRAG DRAG SOLO, Spooner instructed the dancers to change into their rehearsal clothes and perform for the last time the choreography that they had spent two months learning. Shot through the gallery’s glass wall in a simple, archival manner—straight take, sequence by sequence—this silent film distills one episode of their accumulated repertoire as the performers attempt to stay intimately bound together while remaining fiercely separate. Through this intersection of bodies and architectures of management, Spooner examines how power pre-sents itself when it comes into contact with the human body. The film itself is a contingent object and in its muteness absorbs and is affected by the external sound in its proximity.

DRAG DRAG SOLO, 2016

Single-channel projection, daylight bulbs, double-sided room-dividing screen, color; 11:20

min

Courtesy the artist; gb agency, Paris; and ZERO, Milan

For nearly fifteen years, Ryan Trecartin (b. 1981) has uniquely captured the transformative and shattering effects of digital culture on bodies, subjectivities, communities, and narrative structures. His videos from the early 2000s were brightly colored, cacophonous melodramas, created and performed by a close group of friends and often distributed through the then-nascent platform of YouTube. Over time Trecartin’s works have evolved into deceptively complex epics, presented in architecturally ambitious environments. Although his works appear at first glance to be manic streams of consciousness, in reality they are carefully scripted and constructed universes where each character’s appearance, speech, rhythms, and motivations mirror, exaggerate, and critique aspects of our own increasingly nightmarish world.

Item Falls is one of a body of works Trecartin created in 2013 that was shown at the 53rd Venice Biennale. The series of videos comprise a dizzying mix of performance and digital animation, in which a group of highly stylized yet familiar characters enacts a variety of surreal scenarios. Item Falls takes the form of a reality show competition whose participants are ostensibly auditioning to join a boy band while reflecting on notions of status, authenticity, the nature of reality, and free will. As in much of Trecartin’s work, the posthuman characters in Item Falls are conduits for our own very real aspirations and anxieties around constructing identity amid networks of culture, capitalism, and technology.

Item Falls, 2013

HD video, sound, color; 25:45 min

Courtesy the artist; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Sprüth Magers

In her films and installations, Laure Prouvost (b. 1978) unhinges commonplace connections between language, image, and perception. She foregoes traditional linear narratives, exposing the unstable relationship between imagination and reality and allowing audiences to engage provocatively with the surreal. In her films, Prouvost exploits the errors and misunderstandings generated by language in text and speech, as well as the slippages in meaning between images, objects, and words. She often addresses viewers directly, manipulating their senses through sharp staccato edits, grammatically wonky directive syntax, and interspersed fragments of sound.

Prouvost’s video Into All That Is Here (2015) appears ominous at first. The camera moves between a variety of outdoor locations: caves, jungles of dense foliage, a muddy clearing of sorts. Flashing orbs of light, like the spectral “ghost spots” that sometimes appear in photographs, surface to the center of the screen and gradually grow larger, intensifying the sense of ill-fated adventure. A soft-voiced narrator instructs the unseen protagonist to go “further,” “deeper,” as on-screen text concurs: KEEP DIGGING...COME CLOSER...KEEP GOING. Closer to what? Suddenly the video bursts, almost orgasmically, into an explosion of images of flowers, lips, and spewing water; and then opens onto a fast-paced sequence of quick cuts of bodies, plants, and more flowers. Nature and desire coalesce in strange combinations (IT WILL BE PURE LUST, says the on-screen text as fingers enter floral orifices). Prouvost deploys language and rhythm to render the natural environment pornographic and to uncover sensuality within today’s technological onslaught of images—that is, until they disappear.

Into All That Is Here, 2015

HD video, sound, color; 9:42 min

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery

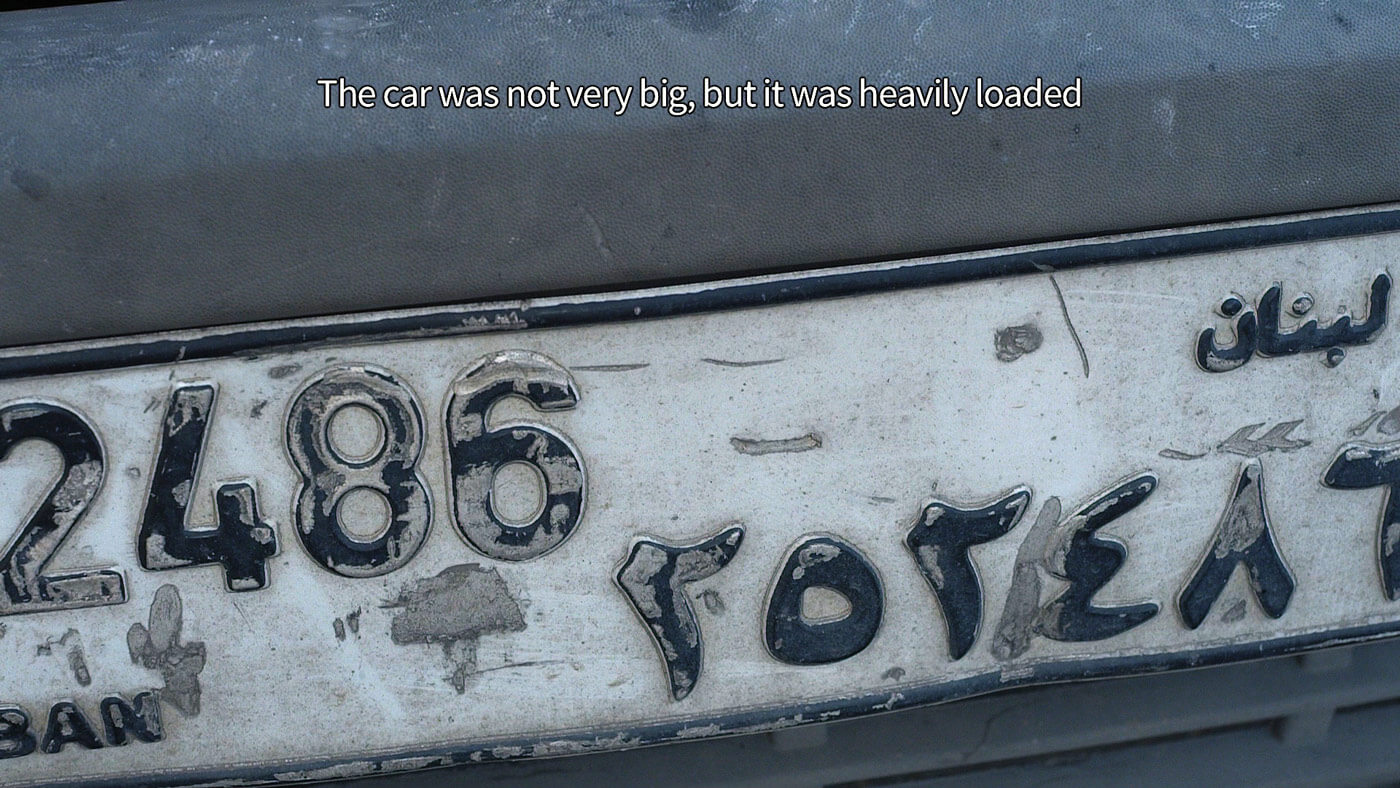

Through role-playing, ventriloquism, and mischievous takes on autobiography, Mounira Al Solh (b. 1978) produces works that often question concepts of identity, subjectivity, and gender. Al Solh is also sensitive to the politics that are embedded in the everyday. As she has explained, growing up in Beirut—a city deeply divided by religion and politics, and host to a civil war from 1975 to 1990—propelled her to “explore critical tactics of inhabiting or surviving unstable times.”

In Al Solh’s video work, Now Eat My Script (2014), the narrator introduces a writer who has failed to write a script for a new video—perhaps, as the setting suggests, the very video we are watching. Instead, the writer has been observing the waves of Syrian refugees (of which there are roughly one million now living in Lebanon) arriving in the streets outside of her Beirut apartment. Midway through the video, the narrator recalls her own family’s experience fleeing Beirut for Damascus during the Lebanese Civil War. Her memories focus on the exchange of food items during this period, and the camera pans slowly, first over an overstuffed, old car parked in the street, and later over a slaughtered lamb carcass neatly laid out on butcher’s white paper. In remembering past exchanges as well as more recent ones among family in Syria and Lebanon, the narrator wonders whether trauma can be consciously lived, or even recorded in a non-voyeuristic way. “Of course you can report on events,” she notes, concluding that perhaps this is “the most difficult and most useful thing you can do.”

Now Eat My Script, 2014

HD video, sound, color; 24:50 min

Courtesy Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut

John Akomfrah’s (b. 1957) Vertigo Sea (2015) draws on historical and contemporary narratives to express the ways in which the Atlantic has dominated cultural imagination for hundreds of years. As in much of Akomfrah’s recent work, Vertigo Sea combines original and archival footage—gleaned in part from the BBC Natural History Unit—with an elaborate composition of music and sound, punctuated by quotations from diverse philosophers and writers. The film outlines the complex intersection between ecology, economics, and politics, and features graphic scenes documenting the history of whaling alongside quotations from Herman Melville’s classic novel, Moby Dick (1851), and Heathcote Williams’s poem “Whale Nation” (1988).

Akomfrah was originally inspired to create Vertigo Sea after hearing a 2007 interview with a Nigerian migrant to Europe who barely survived the perilous sea crossing that has claimed the lives of thousands of other refugees. Akomfrah treats the Atlantic as a site of historical trauma, drawing on archival images and accounts of the horrific realities of the slave trade. Spectacular imagery of waves and wildlife contrasts with scenes of political violence and environmental destruction. In original footage shot in the Faroe Islands, the Isle of Skye, and Norway, isolated figures echo the romantic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. One of these figures represents Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–1797), a former slave who bought his own freedom and then chronicled his harrowing experiences in his autobiography, a key text in the successful abolition movement in the UK. Equiano’s presence haunts the physical and temporal landscapes of Vertigo Sea, positing the Atlantic as a crucible of memory, power, and loss.

Vertigo Sea, 2015

Three-channel HD video installation, color, 7.1 sound; 48:30 min

Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

The work of Anri Sala (b. 1974) questions appearances to expose the paradoxes of time, the limits of perception, and the often-invisible traces of historical change. While the artist’s early films borrowed documentary tropes to examine the intersections of ideology and language, Sala’s later work favors sound and music as nonverbal modes of expression capable of conjuring images, rousing nostalgia, and communicating emotions. In some of these works, Sala employs repetition or a static perspective to build a sense of suspension; in others, music resonates as a requiem for failed modernist ideals or the histories embedded in architectural spaces.

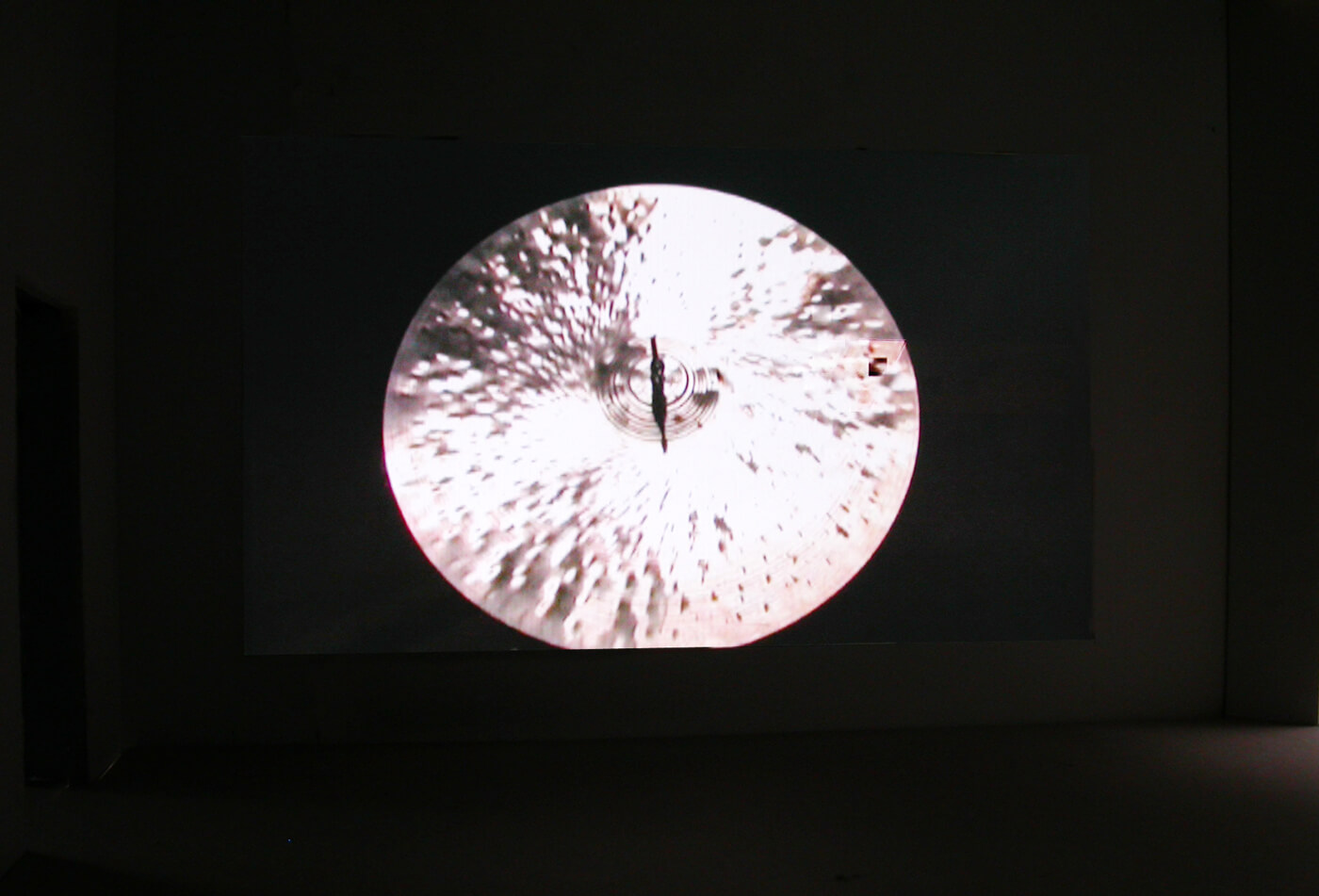

Sala’s Three Minutes (2004) is a silent but mesmerizing meditation on the visual distortion of light, visible as a flickering strobe light on a reverberating cymbal. In this abstract scene, Sala has stripped this instrument of its sound and rendered it purely visual—a shift that radically alters its identity and emphasizes its hypnotic potential. Three Minutes also offers a curious allegory of failed memory and lost information. In parts of Three Minutes, Sala used a strobe light that flashes one hundred beams per second, but his camera recorded only twenty-five frames per second, so the resulting video is an imperfect document. The light that Sala casts on the cymbal also creates a paradox for the viewer’s perception. While light is always associated with the virtues of knowledge and enlightenment, Sala’s work reminds us that light can also be a source of blindness and opacity.

Three Minutes, 2004

Single-channel video projection, color; 3 min

Courtesy Hauser & Wirth; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Maha Maamoun (b. 1972) created 2026 (2010) out of her research into the limits of language and imagination, and draws from Mahmoud Uthman’s 2007 novel The Revolution of 2053, a story set amid current events in Cairo featuring a photographer as the protagonist who can see the future of what he shoots. For Maamoun, this character recalled the science-fiction time traveler in Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), an experimental film composed almost entirely of black-and-white stills. Pairing the formal qualities and iconic time traveler scene of La Jetée with excerpts from Uthman’s novel, Maamoun’s video centers around a time traveler who, suspended in a hammock, describes a view of the Giza pyramids in 2026. While his vision is definitively futuristic—spherical crystalline buildings are linked by glass bridges, and with the sweep of a hand, food is summoned from a hologram patch on a dinner table—the dystopic aspects of the future he visits seem to echo the economic inequalities and social unrest of contemporary Egypt.

The protagonist of 2026 recounts being at an opulent private banquet and looking out on the pyramids’ plateau. He notices, however, that a faint line encircles this lavish setting: a massive video screen masks the crumbling old city and informal settlements, making the pyramids the only landscape that is not digitally rendered. He continues to relate his observation of a scene beyond the wall in which skeletal, hysterical children chase an armored car, clamoring to enter it, until part of the wall opens up to release bags of food. As the children wrestle over the provisions, the car escapes to the other side of the wall, from which side it appears as a glass window simply looking out onto the pyramids.

2026, 2010

Video, sound; 9 min

Courtesy the artist and Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

Hassan Khan (b. 1975) produces work imbued with the historical context, lived experience, and cultural specificity of modern-day Cairo. A musician as well as a visual artist and writer, Khan composed an original music score in the folkish shaabi style that plays a central role in Jewel (2010). Shaabi, a form of Egyptian popular music that literally means “of the people,” emerged in the second half of the twentieth century, and is a subject of fascination for Khan. He sees shaabi, which has appeared in his other works such as Dom Tak Tak Dom Tak (2005) and in his writing, as a radical point of rupture disguised as popular music—capturing, in his words, an “automated moment of civilization...where obscenity and sanctity can coexist in an intense contradiction that is not contradictory.”

In 2006, Khan witnessed two men dancing in the street around a home-made speaker with a flashing lightbulb attached, which became the inspiration for Jewel. Khan transcribed that memory into a filmed scenario, incorporating two stock male characters—one as a seedy and macho street merchant in a leather jacket from the 1980s, and the other as an aspiring office worker who migrated to the city from the countryside. The choreography of the two men is a simulation of everyday Cairene urban culture—the gestures taken from street dances, fights, and traditional ways of greeting. Khan himself describes how the two characters these men embody are not only representations of their class backgrounds but also archetypes of Egyptian history, caught in a mysterious ritual, part mating dance and part social confrontation.

Jewel, 2010

35mm film transferred to HD video, sound, color, paint, speakers, and light fixture; 6:30

min

Original music by the artist

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

The works of Jonathas de Andrade (b. 1982) consider how Brazilian national identity and labor conditions have been constructed against a backdrop of colonialism and slavery. De Andrade’s works also attend to the ways in which attitudes and emotions are shaped and governed by images, social conventions, and political ideologies. In his diverse examinations of Brazilian culture and history, he reinterprets the methodologies of education and the social sciences, using nuances of fiction, artifice, and appropriation to undermine assumptions and confound the sensation of truth.

De Andrade’s O peixe [The Fish] (2016), borrows the style of ethnographic films in its depiction of what seems to be an intimate ritual among fishermen in a coastal village in northeastern Brazil. De Andrade’s camera follows individual fishermen as they catch and then hold their prey to their chests. Alternating expressions of domination and pathos, the fishermen forcefully yet tenderly embrace each fish until it stops breath-ing. This ritual-like gesture, however, is one that the artist has invented, as if to push a deliberately exoticizing portrait to the limits of plausibility. While the ostensible subjects of O peixe are the fish and fishermen depicted, the absence of language and text in the film generates a poignant ambiguity and invites a range of interpretations: one might feel empathy and grief in witnessing death, or heartened by an expression of solidarity with the natural world, or captivated by the peculiar sensuality of this animistic rite. Beneath these responses, however, lurks an understanding that this gesture disguises violence as benevolence and suggests a symmetry between the power that humans wield over other life forms and the power they wield over one another.

O peixe [The Fish], 2016

16mm film transferred to HD video, sound, color; 37:06 min

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York, and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Raised by a family of professional thespians and artists, Ragnar Kjartansson (b. 1976) draws from popular music, the conventions of dramaturgy, and the history of Icelandic and Hollywood cinema to compose works that are grounded in poetic gestures. Often blurring the boundaries between reality and illusion, Kjartansson plays with fakery and pretenses of sincerity that reveal the genuine emotion inherent to playful pretending.

Kjartansson’s performances, which range from hours to days, are feats of perseverance that recall performance art of the 1970s that emphasized durational experiments and tested the physical and psychological limits of the artist. In A Lot of Sorrow (2013–14), rather than casting himself as the leading man as he usually does, Kjartansson partnered with the indie rock band The National. “Sorrow,” from their 2012 album High Violet, was performed over the course of six hours at MoMA P.S.1 in New York on May 5, 2013. The protracted repetition of the song becomes a transcendent mantra or earworm, stuck on loop in the minds of the enthusiastic audience members. As the National soldiers on without pause, Kjartansson tends to them, bringing out trays of coconut water, Coronas, and pork-rib sandwiches. Their momentum finally breaks after vocalist Matt Berninger’s ninety-fifth iteration of the morose ballad. A Lot of Sorrow is a poignant act of live sonic sculpture that embraces the generative potential of repetition and the improvisation that results.

A Lot of Sorrow, 2013–14

Single-channel video, sound, color; 6:09:35 min

Original performance occurred at MoMA P.S.1 as part of Sunday Sessions

Courtesy the artists; Luhring Augustine, New York; and i8 Gallery, Reykjavik